Summer beckoned.

Twenty-seven students could hear it out the window, kicking at spring’s heels to move on. It was the last day of classes. The students’ final projects, printed out and punctured with a Swingline, were now in their professor’s black leather briefcase. For some, it was the last day of college. Ahead was vacation, beaches, beers, flings, jobs, careers—the last thing anyone expected was that they were all about to become authors.

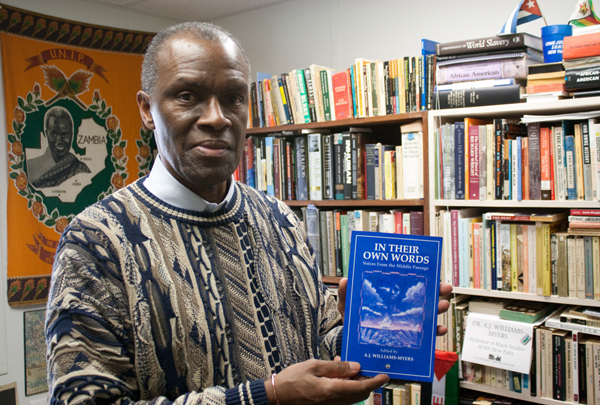

“After I read their papers, I was stunned,” said Professor Albert Williams-Myers. “I said to myself; ‘This needs a larger audience.’”

So he organized them into a manuscript and submitted it to a publisher.

The result was the book In Their Own Words, a fictionalized first-person account of conditions on “The Middle Passage” (the name given to the journey of slave ships from Africa to the Americas) from the points of view of 27 SUNY New Paltz students.

It started as a final project for Williams-Myers’ 2006 course, “Historical Terrorism Against Native Americans and African Americans.” He told his students to re-imagine life on a slave ship traveling over the Atlantic Ocean. When he went to grade the papers, what he found in his black leather briefcase were, in his own words, “the cries from those slave ships crossing that time barrier and linking up with the present.”

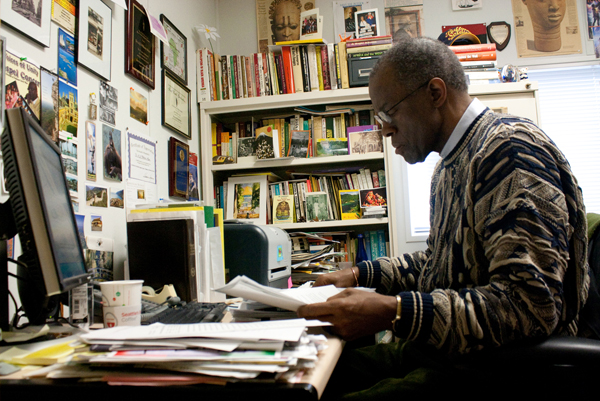

This, Williams-Myers believes, is what sets himself apart from other history professors—he knows how to inspire students to reach out and grab history, instead of trying to force it into them. He believes that the best way for students to learn history is if they teach it themselves.

Therefore, he organizes his Black History I course so that students teach the entire second half of the semester. Classes are based not around lectures, but around student presentations and class discussions—Williams-Myers is there only to guide and mediate the discussions.

Williams-Myers has been a professor at SUNY New Paltz for 31 years. This semester he is teaching three courses. Two of them—Black History I and Introduction to Africa—are courses he teaches every semester. The third is one of his own creation called Race and Racism in History. He describes it as a “socio-political course with a historical backdrop.” For him, there is also a personal backdrop.

An African-American growing up in Georgia in the 1940s, Williams-Myers said he was confronted daily by racism; the poor quality of black schools in his small, segregated town of Edison injected the idea that white was superior to black. According to Williams-Myers, both white and black children, including himself, absorbed this notion as fact. In 1952 his parents decided that he should be educated in a better environment. They sent him to an acquaintance in New Jersey—a white priest—who adopted him as his son. Albert was 13.

Attending school in New York City, a still-segregated but comparatively progressive world, changed Albert’s perception of white and black. He had a white father and played with white friends. He attended church with white and black people sitting side by side.

Attending school in New York City, a still-segregated but comparatively progressive world, changed Albert’s perception of white and black. He had a white father and played with white friends. He attended church with white and black people sitting side by side.

Although never out of the reach of racism, Williams-Myers began to put the brutal south behind him.

At the age of 22 he took a road trip from New York to Arizona with his brother, James, and Janice, his wife-to-be. They stopped for breakfast at a truck stop outside of St. Louis. It was an experience that, as Williams-Myers put straight and direct, “shook us.”

“We went in and sat down at the counter,” Williams-Myers said. “Janice was looking at the menu. The woman behind the counter came over and said ‘Only orders to take out.’ Janice didn’t understand. So I said ‘Janice, it means we cannot sit here in this restaurant and eat. It means they do not want us in this restaurant.’”

Memories of his childhood, the segregation and injustice, came flooding back.

“Discrimination is something that a person of African descent, sooner or later, experiences in their lifetime,” Williams-Myers said. “It is inevitable in the society we live in.”

After four years at Carleton College in Minnesota, Williams-Myers joined the Peace Corps. He was sent to the African country of Malawi, where he worked in child health care. He also began developing an interest in his African roots.

“What excites me about studying history,” Williams-Myers said, “is its ability to come alive—to read about past events, interpret them, and to get into the minds of those that lived at that time. It gives you a better idea of who you are.”

Nobody has a better idea of who Williams-Myers is (at least in the familiar sense) than Zelbert Moore, another professor of Black Studies at SUNY New Paltz.

“Albert has a passion about teaching and research,” Moore said. “He gets very serious and I kid him about it. But maybe it’s only because I envy his passion for teaching.”

For 27 years, Moore has worked down the hall from Williams-Myers. According to Moore, their relationship is based on one very lucky coincidence. As graduate students in 1977, they separately attended a conference of the African Studies Association, held in Philadelphia. They met and got into a discussion about African-American history. Then they parted ways. Six years later, Moore arrived at SUNY New Paltz for a job interview. He walked into an office in College Hall and saw a familiar face. Williams-Myers was conducting the interview.

Recognizing a long-lost friend in an unexpected place is what, to Williams-Myers, the experience of studying history is. He uses the word “magic” to describe these moments—when past events transcend time and history comes alive. And when the cries from slave ships connect with students living 300 years later, and pour out of their pens in their own words, there is no better word.