A current employee at the Rockland BOCES Tappan Zee Elementary School

speaks to her numerous positive experiences, despite the facility being under-

funded.

My older cousin Ryan is severely autistic. He was adopted from a really neglectful household.

He couldn’t speak until he was seven when he was able to get proper services. He started with

sign language, then little sentences. Now at 30, he has to take speaking breaks. It’s so special

seeing that progression.

This summer, I worked in the Rockland BOCES Tappan Zee Elementary School with boys ages

five to seven on the spectrum from mildly behavioral and functional in society, to people who

need assistance for the rest of their lives.

One little boy, Luca, was a runner. What I was doing wasn’t even teaching. It was more like

catching him. You have to drag the chair out, scoop him in, squish it so he can’t move, and then

you drag your chair behind him and hold him there with your arms and legs wrapped around

because he has such severe ADHD.

There’s also Manny, my favorite person to see in the hallway. He’s what the teachers call a mare.

They’re little boys who are like “Hehehe, hello. Good morning. Nice to see you. How are you?

How’s your day going?” and will blow kisses. But then they’re hell in the classroom.

There’s such a wide range of kids at that school, with different abilities and needs. Nothing

works for every single one. If you’re trying to play a game, half the kids aren’t going to be able

to play. During sight-word activities, it’d be like “Everybody say ‘see.’ Everybody says ‘the.’

Everybody says ‘both,’” while the nonverbal kids would be in the back, unable to participate.

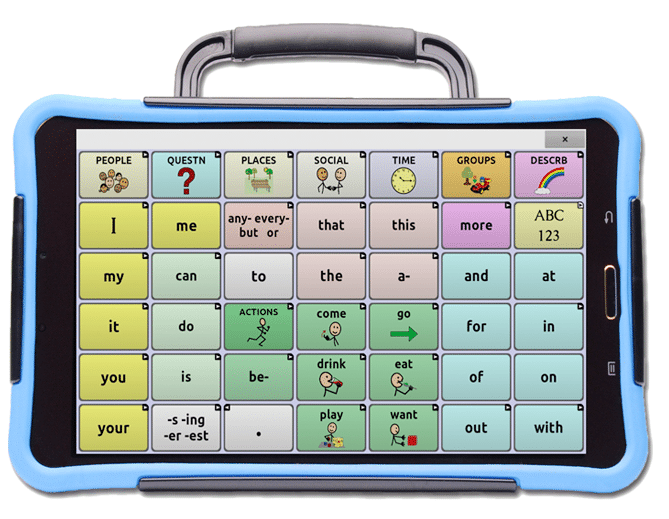

Dean, one of the nonverbal kids, was my best friend. He was sweet, cuddly and quiet. He doesn’t

talk. He has an Augmentative and Alternative Communication, or AAC device. Dean also has

auditory and sensory sensitivities. He doesn’t like loud sounds. He doesn’t like crying or things

falling over. If he gets triggered, he will try to gouge someone’s eyes out or stick his hands in

their mouth to get them to stop talking.

I had crazy bruises all up and down my legs.

But the school is underfunded. We don’t have the resources we need for necessary services, like

occupational and physical therapists, speech-language pathologists and psychologists. Plus,

autistic children need a lot more sensory tools, like bikes for fine motor skills, squishies and pop-

its, or AACs and headphones. Those were hard to find, so Dean went without.

One time when Dean didn’t have his AAC, he signed “I need water.” That was the first thing he

said in sign language. I jumped up and was like “Oh my God, you spoke!” and we danced

together.

Now I want to give others, like Dean, the crucial support Ryan had that they’re missing. So, I

started teaching some of my kids ASL—basic things like how to spell their names, I’m hungry,

I’m tired, all those words that will help them explain how they’re feeling. It wasn’t much but it

was a start and it was really special.

Those kids are the purest forms of human beings. I love them so much. They deserve better.