By Lisa Di Venuta

Suzanne Giller Federman was born in France in 1941, right as World War II was beginning to turn her family’s life upside down. She joked to the audience, “I always asked my mother why she thought that was a good idea.”

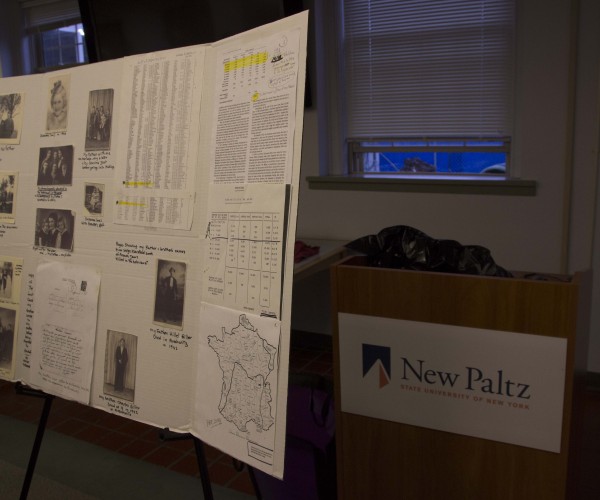

Federman and her husband Henri were both “Hidden Children.” They survived the Holocaust as Jewish children because brave families took them in. Federman spoke to a packed house in the Honor’s Center on Monday, April 20, telling her story of survival. Despite the brutal subject matter, Federman remained composed. She has a jovial spirit, and lightened the story with jokes. “Why is nobody sitting in the front row,” Federman asked in the beginning of her lecture, tongue-in-cheek. “Oh, that’s right, nobody likes to sit in front at these things.”

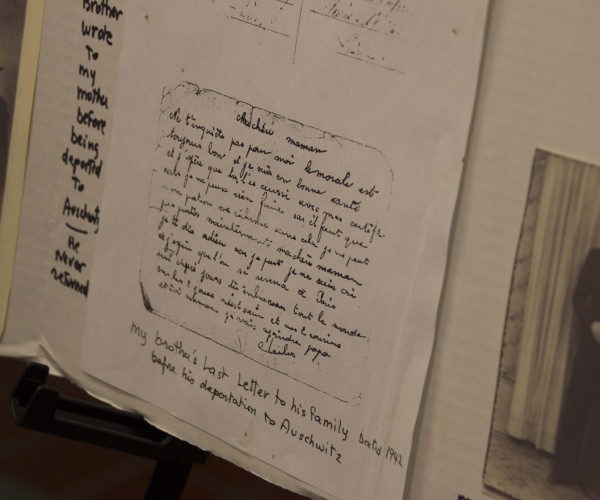

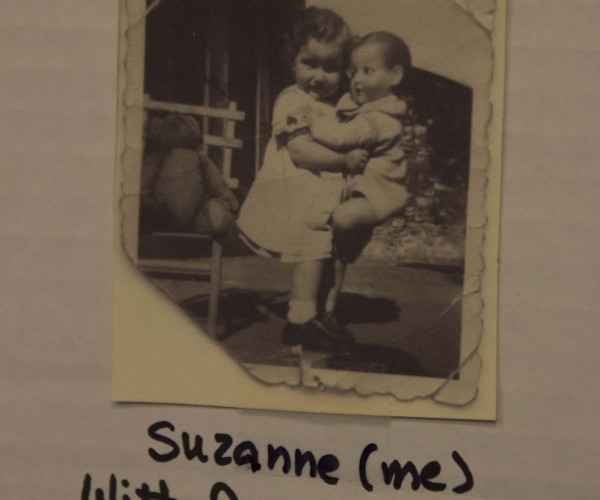

Federman was only a baby when she and her family had to go into hiding. While her brother and father were arrested and sent to Auschwitz, her mother received a pass because of a law stating women with children under 2-years-old could stay behind. However, they were not allowed to live a normal life.

Jews in Paris at that time had to register, and Federman’s mother and sister were forced to wear a yellow star sewn to their clothing indicating their religion. Soon, Jews were forced to move from their homes. Federman’s mother found a way to get false identification papers, and the family went to hide with some good Samaritans in Paris. Federman noted the similarity of her story to one of the most famous Holocaust victims, Anne Frank. Her mother tried to keep her two small children quiet in a small room.

“We had to pack in such a hurry, that my mother forgot my sister’s doll,” Federman said. Her sister cried so often because of this doll that their mother risked her life to go retrieve it.

“Our apartment was put under seal,” said Federman. This was a practice used by the Nazis to ensure that no Jews returned to their homes. Police would seal the doors shut with wax, and if the wax was broken, they would know someone tried to enter the home. Federman recalls how incredulous the doorman was to learn of her mother’s decision to return for the doll.

“My mother knew it was dangerous, but it didn’t matter. My sister was going to drive her crazy without that doll.”

Of course, as an infant, Federman did not remember these things. She told the story as it was told to her. Soon, however, she started to remember. She said as a result of her trauma, memories began to form sooner than they would otherwise.

Federman and her sister were soon sent to a foster home in the country. She had a friendly foster family. Federman remembers putting barrettes in the hair of her foster father — her godfather, as she calls him.

Although she has lighthearted memories, she also has horrible ones.

“There wasn’t enough heat or food,” Federman said, remembering her foster parents tried to make due with hot bricks to warm her bed.

Another time, Federman and her sister — who, with blonde hair and blue eyes, did not look Jewish — were standing outside their school, and a brigade of Nazis walked by. One of the Nazis patted her sister on the head. Her sister was horrified.

By the time the war ended, Federman was reunited with her mother. She remembers being confused as to who her mother was. The 4-year-old Federman and her 11-year-old sister were soon sent to a camp for Jewish children outside of Paris. This camp, run by Palestinian counselors, was a place where Jewish children could be cared for while their parents recuperated. Federman remembers this camp made her feel like it was “OK to be a Jew.” She learned her Hebrew prayers, and went on long walks in the countryside.

After this camp, she was sent to another one — this time, in Belgium.

“I was seen by doctors and dentists for the first time,” Federman said. The children were treated to breakfast at this camp, and Federman can still remember the smell of hot chocolate — a luxury she had never encountered before.

The children’s photos were put in a catalog, and Federman’s picture was chosen by a couple named Jeanette and Max. Federman was spoiled, she said, and fed well by this couple. They were Christian, and Federman remembers going to church with her foster mother and learning Christian prayers — just to make her happy.

She was confused again when reunited with her biological mother. Federman’s sister had been sent to a family in Sweden, so she also lost touch with her. When she first saw her sister again, Federman remembers kicking her — self defense was one of her earliest instincts, after a life on the run.

“My story is not as horrible or sad as other stories you have heard,” said Federman. But she was still raised by strangers, constantly asking the adults in her life, “What’s your name?”

She still lost her brother, father, and aunts and uncles.

Towards the end of her story, Federman pulled out a replica of a Jewish Star, and pinned it to her lapel. She grew somber. “1.5 million children were exterminated in the Holocaust,” she said. “Some kids didn’t get to go back to their parents.” It is clear that Federman’s early childhood has defined who she is as a person.

Federman’s life grew stronger, and her later memories are happy ones. She told the audience about meeting her husband in New York, and falling in love. Her husband was also a “hidden child”, and the two of them forged a life in America together — a life that very easily could not have happened.

“It was thanks to luck, and a few righteous people,” said Federman. Thanks to the people, who hid Federman and those who hid her husband, she is now a great-grandmother.

When asked by a student where she feels most at home, Federman replied, “The United States is closest to my heart.”

Federman chooses to share these difficult memories because she does not want them to be forgotten. She has found that many young people do not know much about the Holocaust. Surprisingly, a group of Israeli students were in this category. When Federman told her story to them, they just asked, “Why didn’t you fight back?” Federman recognizes that this is largely because of the way Israeli children have been brought up. She said, growing up in the Holocaust, “We were trapped. Totally trapped.”

Federman is able to tell her traumatic story because she hopes it will help prevent other acts of genocide in the future. While her early life may have been wrought with heartbreak, she chooses to carry the good memories with her.

“I did not learn to hate,” said Federman.

This June will be the 55th anniversary of the end of the Holocaust.

Check out the first part of this two-part lecture series, Surviving World War II.