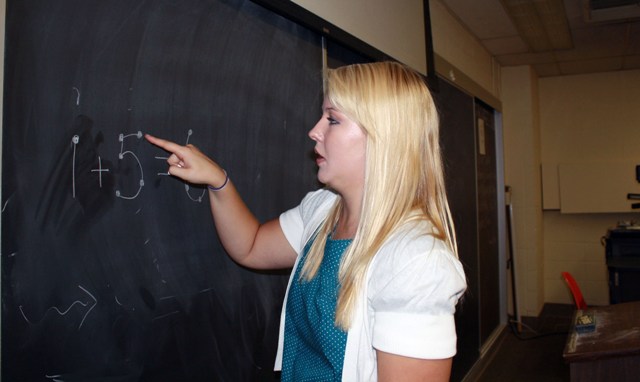

It is 7:30 a.m. on July 6. Ashley Barraud, 19, hops into her green Toyota Camry and begins her 25 minute drive to Clayton Huey Elementary School in Center Moriches, Long Island.

It is 7:30 a.m. on July 6. Ashley Barraud, 19, hops into her green Toyota Camry and begins her 25 minute drive to Clayton Huey Elementary School in Center Moriches, Long Island.

The drive is familiar to Barraud who attended the school as a child. Upon her arrival, the school is childless. At 8 a.m. a school bus pulls up in front. A decade ago the bus would have been filled with Barraud’s peers. On this morning, a group of autistic children arrive for their summer program.

Barraud, a business-minded individual, was not always particularly drawn to children. Through working as a paraprofessional to autistic children, she has learned a great deal, not only about children with special needs, but about herself.

Five days a week, Barraud arrives at Clayton Huey Elementary School a few minutes before the bus drops off eight children. The paras, the children and the lead teacher go for a stroll around town and then the children eat breakfast. Barraud and the other paras ask their children to write today’s date, a task that should be fairly easy to these fourth-, fifth-, and sixth-graders. Most struggle with it, answering out of context, some not answering at all. Two non-verbal children patter at their Touch Talkers—a computer that answers for them based on their touch.

Barraud’s previous summer jobs consisted of retail positions. She had done some babysitting for her neighbors, but had never worked with special needs children. When a semester abroad in London cleaned out her bank account, she searched for a second job.

Her brother Peter Barraud, 24, had worked at the school previously and encouraged her to apply for the para position she was later granted.

“The other paras were mostly teachers or education majors,” said Barraud. “I’m a business major, but I don’t want to be limited to just business. That’s just not me.”

The program Barraud worked for is an 811, state mandated, 10-month program for autistic children with a required summer school. Barraud was rotated eight children throughout the course of a work week. Over time, she became fond of each child in a different way.

The program Barraud worked for is an 811, state mandated, 10-month program for autistic children with a required summer school. Barraud was rotated eight children throughout the course of a work week. Over time, she became fond of each child in a different way.

“They all had their moments and days when they decided they liked you,” said Barraud. “Those were good days.”

There are different types and degrees of autism. Barraud saw a spectrum of autism in the children she worked with. During “Work Time” every child did something different based on his or her ability level. High-functioning children would solve math problems and identify language arts. Low-functioning children would practice basic tasks such as sitting and standing. Their abilities differed depending on level of function.

“One low-functioning girl had to be prompted with a raisin to stand up,” said Barraud. “She taught me to have patience, not only with her, but with everyone, even with myself.”

Children with autism tend to be overly sensitive. A commonality in children with autism is to “stim.” Stimming is a repetitive action that stimulates one or more senses. Stims can be auditory, visual, smell, or any other sense. One of Barraud’s students had a visual stim that made him obsessed with fonts.

“We would pass a shop window on our morning walks and he would shout ‘Arial Round,’” said Barraud. “The amazing part was he was always right.”

One boy would “TV talk.” TV talking is when a child mimics voices he has heard in cartoons, on TV, or in video games. “I would ask him a question and he would answer with a line from ‘SpongeBob’,” said Barraud. “It was hard not to laugh sometimes. Some of the children were so smart, just in different ways.”

One day on a library outing, a high-functioning boy began bullying a low-functioning boy. Barraud told the boy he would lose special activity for bullying after he was already warned to stop and continued. He then began hitting himself and insisting that Barraud had hit him.

“It was the most stressful 20 minutes,” said Barraud. “I wasn’t angry. It just made me second guess my choice to work there. I didn’t know how it was going to reflect on me. I knew I didn’t hit him, and I knew the teacher knew. I was just sad that he would say that.”

It is the end of the day, and time for Barraud to gather the children together for the “Goodbye Circle.” In preparation for the bus to take the children home, someone’s address is said aloud in hopes the child who lives there will recognize it. One boy knows the address of every child in the class. Some children don’t ever recognize their addresses, even though they are repeated everyday.

“The kids aren’t going to hug you and run to you,” said Barraud. “That is not the rewarding part of the job. They could learn something one day and make you so proud, and the next day it is like they never learned it at all. A small conversation, even for a few minutes, that’s rewarding.”

Even if she doesn’t work with autistic children in the future, Barraud feels the experience she has gained while working with autistic children has and will continue to benefit her in many areas of life.

“I’ve learned never to judge,” said Barraud. “If you see someone acting out in public, don’t judge him or her. You can’t always see there is something wrong with someone just by looking, and if that person is autistic I know first hand there is so much more to him.”

Even though it wasn’t her typical summer job, Barraud does not regret her decision to work at the school.

“Get out of your comfort zone,” said Barraud, “Try new things because you’ll have great experiences.”